CCORDING to the newspapers of the country,

Chicago stands at the head as the great divorce center of the United States, and its courts

have attained such a notoriety for releasing man and wife from a bad matrimonial bargain that

hundreds go there from other states every week, thinking that all they have to do to secure a

divorce is to make their complaint, pay a lawyer and tell their story in court. But Chicago

does not stand alone in this somewhat peculiar industry, and in proportion to her size

Minneapolis courts turn out more divorces that Chicago ever thought of. Just why this is so

no one appears to know, but it is probably the effect of the climate, which has a thousand

and one other equally unpleasant things to answer for. Minneapolis has some of the most

sensational divorce trials that ever came into any court, but in many instances the particulars

of them have never reached the public ear, the case being "too horrible for publication." The

court records, had they power of speech, could tell many a sad story and many a ludicrous one.

But it is a decidedly fortunate thing that they cannot tell the contents of their pages, or

many a household would be bent down with shame in consequence. Applicants for divorces are

not confined to the lower and middle classes by any means. Some of the most aristocratic

people in the city have told a story of sorrow to one of the judges. This class of people

generally make an endeavor to have their case tried in chambers, i. e. in the judge's

private room, with all spectators excluded, but greatly to the credit of the judges this sort of

thing is seldom permitted. That it would be decidely unjust is plainly apparent, for in a

court of justice a poor man is to have the same right as a rich man, and where would be the

justice of keeping the divorce of a rich man secret and publishing to the world the disgrace

of a poor man?

CCORDING to the newspapers of the country,

Chicago stands at the head as the great divorce center of the United States, and its courts

have attained such a notoriety for releasing man and wife from a bad matrimonial bargain that

hundreds go there from other states every week, thinking that all they have to do to secure a

divorce is to make their complaint, pay a lawyer and tell their story in court. But Chicago

does not stand alone in this somewhat peculiar industry, and in proportion to her size

Minneapolis courts turn out more divorces that Chicago ever thought of. Just why this is so

no one appears to know, but it is probably the effect of the climate, which has a thousand

and one other equally unpleasant things to answer for. Minneapolis has some of the most

sensational divorce trials that ever came into any court, but in many instances the particulars

of them have never reached the public ear, the case being "too horrible for publication." The

court records, had they power of speech, could tell many a sad story and many a ludicrous one.

But it is a decidedly fortunate thing that they cannot tell the contents of their pages, or

many a household would be bent down with shame in consequence. Applicants for divorces are

not confined to the lower and middle classes by any means. Some of the most aristocratic

people in the city have told a story of sorrow to one of the judges. This class of people

generally make an endeavor to have their case tried in chambers, i. e. in the judge's

private room, with all spectators excluded, but greatly to the credit of the judges this sort of

thing is seldom permitted. That it would be decidely unjust is plainly apparent, for in a

court of justice a poor man is to have the same right as a rich man, and where would be the

justice of keeping the divorce of a rich man secret and publishing to the world the disgrace

of a poor man?

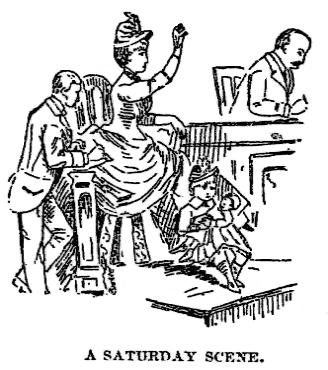

"Divorce day," as it is called in the district court, comes on Saturday, when all the judges,

Messrs. Lochren, Young, Rea and Hicks, are expected to hear some of the cases; that is, if one

of the judges thinks it would be too great a strain upon his nerves to hear all of them.

The grind generally begins soon after 9 o'clock, and it is seldom there is not a

morbidly curious crowd of spectators on hand, ready to take in all the filth and stare

impudently at the parties most concerned. In the majority of the cases which are heard there

is no appearance on the part of the defendant, and the applicant for matrimonial freedom has

an easy time of it. She (if the applicant be a woman) is generally accompanied by one or two

friends, of either sex, and in a great many cases there is present the man whom she will marry

as soon as she gets her divorce. That one unpleasant matrimonial experience does not

discourage a woman, is shown by the marriage license records. Thus far this year there have

been nineteen licenses issued to men who intended to wed women who had secured divorces in the

same court from which the license is issued less than one month previous.

The grind generally begins soon after 9 o'clock, and it is seldom there is not a

morbidly curious crowd of spectators on hand, ready to take in all the filth and stare

impudently at the parties most concerned. In the majority of the cases which are heard there

is no appearance on the part of the defendant, and the applicant for matrimonial freedom has

an easy time of it. She (if the applicant be a woman) is generally accompanied by one or two

friends, of either sex, and in a great many cases there is present the man whom she will marry

as soon as she gets her divorce. That one unpleasant matrimonial experience does not

discourage a woman, is shown by the marriage license records. Thus far this year there have

been nineteen licenses issued to men who intended to wed women who had secured divorces in the

same court from which the license is issued less than one month previous.

The study of applicants for divorce is an interesting one, showing as it does every side of nature, and bringing the virtues and vices, the habits and faults of men and women into full view. In the majority of cases it is the woman who is the appellant, and in nine cases out of ten she either charges desertion, cruel and inhuman treatment or unfaithfulness. Of course there are other charges, but they seldom are embodied in the complaint, and less often do they appear when the case comes to trial. The lack of children is sometimes made the main cause of action in divorce proceedings, but this is very seldom, as the records show that but three such cases have ever been tried in Minneapolis.

If any one desires to see the divorce machinery of the district court in full motion, and hear

many a tale of domestic infelicity, let him go to the court house some Saturday morning, when

there are a large number of cases to be disposed of, and he can be accommodated. In the rear

room, seated in the spectators' benches, he will see a crowd (that is, half a dozen or more)

of women watching for the judge to make his appearance and begin operations. These are the

and among them may be seen almost every kind of woman, from the

pale-faced, sad-eyed little body, who has been kicked around by a brutal and drunken husband

until life has lost all its charms for her, to the buxom, dashing, bejeweled "lady," who has made

her home so uncomfortable for her husband that the poor man was obliged to leave, in order to

get a little rest, or to escape being bankrupt by her extravagance.

and among them may be seen almost every kind of woman, from the

pale-faced, sad-eyed little body, who has been kicked around by a brutal and drunken husband

until life has lost all its charms for her, to the buxom, dashing, bejeweled "lady," who has made

her home so uncomfortable for her husband that the poor man was obliged to leave, in order to

get a little rest, or to escape being bankrupt by her extravagance.

The scene is certainly an

odd one, and as the looker-on watches them he can scarcely help wondering if "all matches

are made" in heaven, and if people do not sometimes make a mistake in picking out their life

(until divorce is granted) partners. Some of the women are tearful, and try to hide their faces

from the curious crowd, and you may be sure that these are the women who have been abused.

Others smile and giggle, and seem to enjoy the notoriety into which they are brought. Many of

the latter class are even now contemplating matrimony, and as soon as their divorce is secured

will wed some man and go through their first experience a second time.

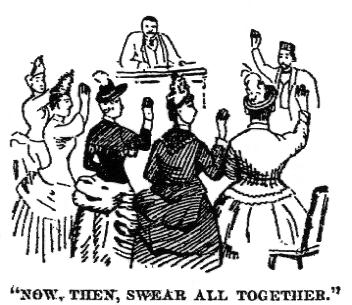

It would be a great saving of time if some means might be devised whereby all the applicants

could be sworn at once. Then there would be no necessity for the clerk to wear out his lungs

and his temper by mumbling to each one as her turn comes:

"Youslmlyswearateviencey'ligivencasenowunnerconseration, etc., s'helpyeGod?"

Half of the women to whom this oath is administered don't understand it, but they think they

do, and that answers the purpose just as well. Mrs. Patience Hardlines is the first applicant

heard. She is as pretty as a picture and she knows it.

So she dresses quietly, but to the best

advantage, and enlists every one with any heart at all, on her side at the outset. "We were

married at St. Paul Jan. 4, 1884," says she, "and soon after came to Minneapolis. After we had

been here a few months my husband began to drink a great deal in spite of all my pleadings.

When he was intoxicated he had a most awful temper, I am sorry to say, and whenever he came

home this way he always beat me and threw me around. On July 24, 1886, he kicked me out of

bed, and swore at me because I was not patriotic. When I told him I was too tired to celebrate

just then, he took me by the hair and dragged me around the room, occasionally kicking me in

the stomach or on my limbs. When I was all tired out and so lame I could not stand up, he

tied me to the bed and beat me with a strap. There are marks on my shoulders now where he

struck me, and you can see them if you want to. I stood it as long as I could, but was finally

obliged to go back to my mother, where I am now living." If the woman's story is corroborated

a divorce is seldom refused her in such a case.

So she dresses quietly, but to the best

advantage, and enlists every one with any heart at all, on her side at the outset. "We were

married at St. Paul Jan. 4, 1884," says she, "and soon after came to Minneapolis. After we had

been here a few months my husband began to drink a great deal in spite of all my pleadings.

When he was intoxicated he had a most awful temper, I am sorry to say, and whenever he came

home this way he always beat me and threw me around. On July 24, 1886, he kicked me out of

bed, and swore at me because I was not patriotic. When I told him I was too tired to celebrate

just then, he took me by the hair and dragged me around the room, occasionally kicking me in

the stomach or on my limbs. When I was all tired out and so lame I could not stand up, he

tied me to the bed and beat me with a strap. There are marks on my shoulders now where he

struck me, and you can see them if you want to. I stood it as long as I could, but was finally

obliged to go back to my mother, where I am now living." If the woman's story is corroborated

a divorce is seldom refused her in such a case.

But when a woman with a story like this tries to get a divorce she is apt to be closely questioned by his honor, especially if her appearance is at all striking, or she looks as if she were just about as fast as a woman can be and still be respectable: "After we were married we did not get along well together, and in consequence we had a number of rows. Once my husband hit me with a book, but he never tried it again, for I nearly choked him to death. About three years ago he left me, and I have not seen him since. Did I give him any cause to leave? Why, what an absurd question. Of course I did not. I never did anything to make him feel bad. All I ever did was to refuse to get his meals for him sometimes, and then because he smoked I would not sleep in the same room with him. He used to complain because I spent so much money for clothes, but la! me! I did not take all his old money. He was a good workman and made $100 a month, and I never used to spend over $50 of this on myself. It was all his fault, Judge, and if he cared for me the way he should he never would have left me."

In many cases the women seeking to be released from their matrimonial ties by due process of

law, bring their children with them into court, and it is not an unusual sight to see half a dozen

mothers nursing their babies, or carressing them if they have outgrown their baby clothes,

while awaiting their turn to pour their story into the ears of the judge. The little ones

sometimes clamber around the desk utterly unconscious of the drama going on, and smile [calmly] at

the judge, who is to decide whether they shall be made half-orphans or not.

mothers nursing their babies, or carressing them if they have outgrown their baby clothes,

while awaiting their turn to pour their story into the ears of the judge. The little ones

sometimes clamber around the desk utterly unconscious of the drama going on, and smile [calmly] at

the judge, who is to decide whether they shall be made half-orphans or not.